PART FIVE

TOP SECRET

Early in May

of 1921, a little more than six months after Reed's death, Louise left

The State

Department, this time headed by Charles Evans Hughes, realizing she was the

only American journalist, whom Lenin and Trotsky trusted, wanted to know what

she might have learned from them, since so little credible information was

available anywhere about what was really happening inside the

The report of the Commissioner's interview, an impressive diplomatic document of four 17 X 11 inch pages, initialed by a half dozen officials who had read it, was buried on June 7, 1921, along with other government documents marked CLASSIFIED, and was not declassified until March 23, 1960.

It contained

nothing at all that might have been considered a threat to national security,

beyond what Lenin had told her. And this

might have been considered a "threat" by the new Warren G. Harding

administration, since .it did not seem to square at that time with

Lenin had

expressed eagerness for trade relations with the

On religion, she told the Commissioner: "The head of the Russian church seems content. He says the church has needed shaking up for a long time." The Russian clergy, however, became incensed when the Bolsneviki placed on the facades of all churches signs reading: 'Religion is the Opium of the People,' and would not permit them to place beside these signs others which say 'Religion is the way of Salvation for the People.'"

Zinoview is

not at all popular in

No matter

what hardships

The Russian people

had a warmer feeling for Americans than for the French, English or anyone

else. A Russian schoolteacher told her

she knew all about

Louise, with a great deal of material in her possession for Hearst newspaper articles, appears to have been careful to provide the Commissioner with very little information, especially the interviews with Soviet leaders, many of whom she had also talked with at the height of the Revolution in 1917.

Upon her return to

Louise happened to be the only one who qualified. She had written a book about the Revolution and had made big headlines. Thus came about the metamorphosis of "a beautiful dupe of the communists" to a roving correspondent for the International News Service, an honor with which went an excellent salary and an unlimited expense account.

The articles and interviews

dealt mostly with the great changes that had occurred in

In the middle of May in 1922,

the Hearst people sent her to

News item in Hearst and other papers serviced by International News Service:

Louise Bryant reported the

conflict between Greeks and the Turks in

Louise did not stay long in

She was on the Hearst payroll for two and a half years, the first year secretly, the remainder as an acknowledged correspondent with her name over the articles she wrote.

When she

returned to

She was nearing her thirty-sixth birthday, had become almost completely alienated from her family and was troubled by a feeling that she had betrayed Reed in going to work for the Hearst people in the first place, even though it was in order to be with him and he was in no shape to be critical by the time she arrived. Her writing soon became dull and uninspired.

She decided she must try to get out of journalism, perhaps get married and have a child while there still was time. The interview with Mussolini, strengthened her resolve to find a way out.

She was

surprised and pleased when she answered the ringing telephone and heard Bill

Bullitt's voice. He was in

She recalled

the first time she met him four years ago. He was at that time still an

important member of the Woodrow Wilson administration, and she had accompanied

Jack to

After assuring

Reed he would do his best to get the government red tape unraveled, Bullitt

looked at her and said: "I've been

reading your articles on

I am not at all certain what all this will accomplish," she had replied. "What I am certain of is that we're tired of having idiotic men make all the laws which control our lives, I do not think anyone could have said it better than Sarah Bernhardt: 'It is ridiculous that my chauffeur has the right to vote and I haven't.'"

When he came into the room, he seemed somewhat ill at ease, and, as if he had rehearsed what he would say, he greeted her with, "Well, now that women have joined idiotic men in making the laws which control our lives, do you think the world is a better place?"

Louise laughed: "No, all we wanted and all we got by the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was the right for idiotic women to join idiotic men in making the laws - that's what equality means, you know."

Bullitt told

her that he was in "diplomatic exile," that he had quarreled with Woodrow

Wilson's top confident. Col. House,

while the Democrats were still in control, and had, for several years, been a

sort of "good will ambassador" in

First, however, he wanted to know something about her association with the Hearst newspapers. (Hearst newspapers were often called "the Yellow Press" because of their sensational headlines and emphasis on crime and scandal.) Louise reluctantly told him a few of the details that made it necessary for her to accept a Hearst offer of employment, and then: "The Mussolini assignment was the last straw. I'm going to resign."

She told him that Mussolini was a repulsive monster, who had the sort of contempt for people which nauseated her. He referred to the Italian people as "the masses" and listening to him talking about "the masses" brought up a mental picture of an overfed early nineteenth century American plantation owner talking about his slaves.

Mussolini, said Louise,, wanted to see "the masses" comfort-able, have jobs, schools, providing they did not get involved in the decision-making process. What they needed, according to Mussolini, was a powerful leader who knew what was best for them.

Bullitt was intensely interested in what she had to say. She said she asked Mussolini why he, the editor of the socialist paper "Avanti," turned to fascism, and discovered, said Louise, “that he was, among other things, also a liar.”

Mussolini told her it was because of the way the German socialists reacted to the Kaiser's call for all-out support of the war against the allies in 1914. For years, said Mussolini, they shouted their slogans, "workers of the world unite, cast off your chains," "end the rule of capitalist exploiters" and so on and on.

But at the sound of the bugle, the waving of the flag, the German socialists led the pell-mell rush to arms. . . they forgot their slogans and began shouting, along with everyone else "Deutchland uber alles."

That was when

the paper "Avanti" began urging Italian support for the allies. But he was lying, said Louise. The truth is the Italian socialists fired him

when they suspected he had been bribed by the French to use the paper to gain

He was sitting next to her when he asked her if she would care to talk to him about Jack Reed and his last days with her. His question acted as an electrifying catalyst. She suddenly realized how lonely she had been and how desperately she needed to feel wanted. A wave of desire overwhelmed her and she began to sob.

He began to visit her more and more often and she began to see in him the strength and direction she had so unsuccessfully been seeking until now to ease the pain and emptiness that Jack's death had left behind. As their involvement deepened, and the anticipation of each night together grew in passionate intensity, she pulled out of her despair and her daydreams and romantic images took control of her thinking. She began to build for herself an exciting, secure and happy life with Bullitt.

Based on wishful-thinking, the future she was creating would be, she was certain, a continuation of the exciting life she had been living, but in a different context. She would again meet important people, but this time as Mrs. Bullitt, their equal, and not as a journalist by special appointment. She would be able to participate in discussions with them and become known not only as the attractive wife of a world-famous diplomat, but also as an intelligent woman, well-informed on important matters.

She was not unaware, moreover, of the practical dilemmas her new life would resolve. She was thirty-eight years old and time was running out for her to have a child - a boy who would constantly remind her of her years with Reed.

Equally important, it would help her become reconciled with her mother. A telegram with news that she had married a man of distinction would surely please her mother and Sheridan.

They were

married secretly in

Bullitt, born in 1891, did not know that she was six years older than he was. Nor, for that matter, did he know much of anything else about her background.

What he did know was that she was more than six months pregnant on December 10, 1923.

LIFE WITH BULLITT

William Christian Bullitt's background and temperament, if nothing else, made the chances practically zero for a lasting marriage with Louise Bryant. It is impossible to imagine a sharper contrast in the environments in which each was born and lived, and in their personalities and sense of values.

Louise, the

granddaughter of Irish and German refugees from hunger and tyranny in

The first of

Bill Bullitt's ancestors to reach American shores was Benjamin Boulet, who came

from

As the years

passed, descendants began to settle in

There was, for

instance, Susan Bullitt Dixon who wrote a history, "The Missouri

Compromise and Its Repeal," which the New York Times described as one of

the great contributions to the history of

As for Bill

himself, he was one of the Philadelphia Bullitts. His grandfather, John Christian Bullitt, came

from

His father was

also a Philadelphia lawyer and political leader, whose great wealth came from

His

antecedents on his mother's side (she was his father's second wife) were also

distinguished Americans. She was a

Jewess, whose maiden name was Louise Gross Horowitz. Her grandfather, Dr. Samuel Gross, a famous

surgeon, is memorialized in

Bullitt was universally admired for his skill in the diplomatic world, and an important member not only of the Woodrow Wilson administration, but also that of Franklin Roosevelt's.

But along with his effervescence, eloquence, charm, and other admirable qualities, Bullitt was egocentric, demanding, never willing to budge from what he had determined was right.

All of this was best illustrated by the problem Sigmund Freud faced with him when they decided to write jointly a psychological study of Woodrow Wilson. Publication was held up for years while they argued over who would contribute what to the book's contents. In his capacity as a friend of the family, Freud later tried without success to halt or slow the deepening of Louise's paranoid schizophrenia.

But all of Bullitt's diplomatic know-how, his ability to discuss brilliantly ways to reconcile conflicts among nations, did not help when it came to converting irrepressible Louise Bryant into a charming hostess at elaborate receptions.

No one knew anything about the secret marriage, except Lincoln Steffens, the close friend of Louise and Jack Reed, as well as Bullitt. But Steffens did not know when they were married. He knew only when their child was born, because he was there. The exact date of the marriage is in Bullitt's secret divorce testimony.

Near the end

of February in 1924, less than three months after the marriage, Steffens wrote

to his sister in

Louise Bryant has been having a baby. They were married last year, telling nobody. While I was in London Louise kept writing that I must come over; she couldn't have the baby without me, and Billy wanted me there too. And the baby was due. Well, I lingered and yet when I did come the baby didn't, and it was only Sunday night that it was born. And it was my baby theoretically. Billy wanted a boy, so did Louise; I preferred a girl. They said that if it was a boy they would keep it, if it was a girl, I should have it. When the labor pains began Billy phoned me. But it was not until the next morning that the baby was born, and it was a girl. Billy phoned me and said that it was not merely a girl; it was a terrible, dominant female. It came out kicking Louise; it made a mad, bawling face at Billy, grabbed the doctor's instrument and threw it on the floor.

"I shall have nothing to do with it," said Billy. "I am afraid of it. You can have it. All I ask of you as a 'parent', is to keep it off the streets. But I doubt that you can even do that. It will do whatever it wants to do. I saw it the next day, and it is a pretty child, a bit red yet, but handsomer than any newborn baby I have ever seen.

If medals were awarded to the best and most dedicated husband during a wife's pregnancy, Bill Bullitt would have won hands down for the almost uxorious attention he lavished on Louise. "He hovered over her like a mother hen," said Ella Winter, Lincoln Steffens' wife. She described Louise as "the pregnantest woman I have ever seen, looking radiantly happy in her maternity gown which must have been fashioned for a Persian queen."

One day Bullitt came home, wrote Ella, and found Steffens reading to Louise. He kissed Louise and sat down beside her. Suddenly he jumped from his place beside her, his face white with anger. He realized Steff was reading from James Joyce's - at that time a very controversial book - "Ulysses". "How dare you read books unfit to print in my home. What effect do you think stuff like that will have on my unborn child?"

As the weeks

and months rolled by, it remained, at least outwardly, a most glamorous life

for Louise Bryant who, during the Russian Revolution, often had to satisfy her

hunger with a cucumber and a piece of herring, in

But during the night, in her dreams, her years with Jack would intrude. He would upbraid her and accuse her of betraying everything he stood for. "What has happened to you, my little sweetheart?" he would say. "Have you forgotten the Irish poets and writers who battled British troops with a sword in one hand and a copy of Sophocles in the other about whom you used to write articles for the Masses? Why did you bring a girl child into the world? Don't you remember our last days together when we reproached ourselves for not having found time to have a child? And you broke down and cried and said you had always wanted a son who would be named John and be like me."

"But

Jack," she would plead, "I've come to love Anne. I didn't really at

first, and was disappointed because it wasn't a boy. Anne is such a sweet child, and so

clever. One day we were taking a walk

and met Dr. Freud, who was lecturing in

Louise would awaken and stare at the ceiling tired, confused and depressed. Jack had accused his "dear little sweetheart" of betraying him, the phrase Russian employ to express affection, respect, sympathy. "Tears will not bring her back to life, little grandmother," says a doctor to a grief-stricken grandmother.

It was true

that only a few days before his death they had talked about their failure to

have found time to have a child, but Jack was by that time a gaunt, human

skeleton and his greatest concern was the welfare of his mother in

She decided

she would talk with Dr. Freud about her dreams. She had interviewed him for the

Hearst newspapers and was beginning to see more and more of him because of Bill

Bullitt's and Freud's joint interest in a book about Woodrow Wilson. What troubled her was that all her dreams

seemed to leave her tired, frustrated and depressed and a vague feeling of

insecurity about what she was, what she is and what she will become. Bill Bullitt, the millionaire diplomat, whose

name was dropped from the Social Register when it became known he had married

the widow of a communist - a radical in her own right - remained a solicitous

and devoted husband and father. When she

decided that what she needed was travel, they began to travel, even though she

had already been to most of the places and talked with, and written about,

kings and dictators and other world leaders.

Their schedule:

They had a home in Paris, another in

Her mother, despite their long estrangement and the apparent lack of maternal warmth in the irregular correspondence that had begun between them in the fall of 1922, had never forgotten that of her five children she had borne, it was Louise who kept fresh her memory of Hugh Mohan, the only man she had ever loved passionately and without reservation. She had hinted several times that she would like to see Louise again. . .Perhaps if she and her husband had occasion to be on the West Coast? . . .

Louise had

planned to suggest to Bullitt a possible trip to

Threats and

other forms of harassment finally forced them to abandon their home and move to

the eastern division point of the railroad at Marysville, near

DISINTEGRATION

As the days and weeks passed, life with Bullitt became more and more difficult. She discovered that his strength, which had initially drawn her to him, also made him overbearing and that what he expected of her was not an attractive, well informed wife who would participate as an equal in significant discussions with important people, but a charming hostess who would smile graciously and unobtrusively at guests as they arrived for receptions. She caught him glancing at her disapprovingly if her laugh rose above the level of others. She began to find dressing for receptions a nuisance, the receptions themselves boring, the people loathsome. She discovered that compared with living with multi-millionaire Bullitt, her dull life with her first husband Paul Trullinger in Portland was almost exciting.

“How wonderful to be free, to be

able to do just what you want and do it when you want," she had said to

herself on reading John Reed's article in a magazine on a streetcar in

The slide to disaster began with quarrels, frequently reprimands by Bullitt about her behavior which he considered undignified for the wife of one in his position. Louise found herself helpless, intimidated, insecure, frustrated and unable to articulate the emotional turmoil his words were creating in her.

He spoke slowly and precisely, never altering his professor style manner of presentation, as though he was explaining the merits of the Treaty of Versailles to Col. House. If she tried to argue, to explain and broke down and began sobbing, he approached her, put his arms around her and tried to console her.

But alone in her room, she brooded and reenacted the quarrel. Here she knew exactly what she should have said to him and what she should have done. Here she was the winner, for here wouldn't he have to admit her greatness, her achievements, her involvement in historically significant events, her ability to win the respect and admiration of world leaders. . .compare all that, Bill Bullitt, with having displeased an over-dressed bitch at a reception.

She began turning to this self-created world in her mind, where she was always the winner, more and more often and remaining there for increasingly lengthening periods. When Bullitt, in despair, turned to Sigmund Freud for help, Freud called it "schizophrenia".

A time came when Bullitt became "real" as she mentally argued with him. Then she would demand to know why he never used four-letter words. Jack, she would inform him, always used four-letter words.

The scenario could have been written by Robert Louis Stevenson and entitled Doctor Jekyll and Mrs. Hyde.

As her schizophrenia deepened, she became wary not only of Bullitt, but also of everyone else who was deeply concerned about her. She would try to convince all of them of her importance. She found herself surrounded by "enemies". A servant with a tray was Bullitt with a gun. This was "paranoia", said Freud. Bullitt told him that in periods when fantasy seemed to have completely replaced reality, she would suddenly come into a room naked without regard to who was present. This Freud called "exhibitionism" - a very primitive form of behavior with erotic connotations.

With Freud's help, Bullitt realized that Louise was a sick woman. He might as well blame her for having terminal cancer as for the spells during which fantasy replaced reality.

Freud had by that time begun modifying the theory that bringing to the surface the causes for mental problems will end them. Helping Louise, said Freud, would be somewhat like trying to put a scrambled egg together. "There are so many things we don't know and may never know. I myself have not been able to determine why I never fail to bring my mother a potted plant on her birthday, but invariably forget a wedding anniversary gift for Mrs. Freud. I also do not understand why I am afraid to cross a street at an intersection with a crowd." Neither could he explain why a beautiful, intelligent, articulate individual should suddenly begin to alternate between quoting Byron and Shelley and hurling the vilest invective at another equally brilliant, articulate individual, then accuse him of attempting to kill her.

In 1925 she suffered an attack of elephantitis and was forced to wear clothes to cover as much as possible the hideous appearance of her skin and to take drugs to which she soon became addicted. By 1926 she was drinking heavily.

Then in 1929, the news broke in all the papers:

And, in 1930:

Little wonder that "no

other details were available." Bullitt's petition for a divorce was heard

behind closed doors by Francis Biddle, who became Franklin Roosevelt's

Attorney-General in 1941. Because of the

nature of the case and the people who were involved, Biddle suggested that the

records be impounded when he recommended to the full Court of Common Pleas No.

5 of

From the records of Case No. 1527, December Term for 1929:

"The parties, William C.

Bullitt and Anne Louise Moen Bullitt, were married in

"The legal grounds for the divorce were 'indignities to the person,' which renders one's condition intolerable and life burdensome.

"Bullitt testified: Mrs. Bullitt began drinking in the winter of 1926-27, and as her drinking became heavy, her hostility toward him increased.

"During the winter of 1927, at the house of Lawrence Langley, he noted this incident: 'A pianist began to play, and when the hostess asked her to stop talking, she stood up and called out that it was an insult to intelligent people to have a pianist interrupt their conversation, and she stalked out of the house in a rage.'

"As time went on, Louise drank even more frequently. She stopped occasionally on his request, but started drinking again soon afterwards. Bullitt pointed out that she was charming when sober, but very irritable when drunk.

"During a visit to their

summer home in

"In June of 1928, the chairman of the Regatta Committee invited the Bullitts to the Harvard-Yale Regatta. As the varsity race began, Louise, who had been drinking heavily, stood up and started to fall overboard (they were sitting on the Chairman's yacht). Bullitt said he caught her and stopped her. He testified: 'She cursed me, saying that she had a right to fall overboard if she wanted to; that I was trying to restrict "her liberty in every possible way.' This exhibition of behavior was performed before thousands of people. Bullitt testified that when they reached their hotel she called him 'a dirty little Philadelphia Jew whose only idea was to persecute her; that I was a miserable bourgeois and could not appreciate an artist like herself and could not appreciate her thoughts or anything she felt about life, and that she could not endure being near me any longer;. . . She took her clothes off and rushed through the hotel stark naked.' Bullitt ran after her and carried her back to the room, although she was cursing and struggling with him. She fell into a drunken sleep, and when she awoke she renewed her attack upon him, claiming she hated him for disapproving of her drinking and wanting to live her own life exactly as she chose. "During that summer, she began drinking at all hours of the day, and drank herself into a stupor two or three times a day.

"While on board the

DeGrasse, returning to

"During their stay in

"One night at dinner with the Duke and Duchess DeRichelieu, Louise was drinking heavily and conspicuously flirting with the Duke. Bullitt testified that he admonished her about such shocking behavior. She responded that "I was just a horrible petty bourgeois who was trying to turn her into a respectable bourgeois wife, which she did not intend to be, and she would go on drinking as she wished.'

"She returned to the house when Bullitt was seriously ill with the flu, but she was drunk, hostile and paid no attention to him. She refused to take care of him, and left with Miss LeGalliene.

The Bullitts went together to

the

Bullitt testified Louise

borrowed $1,000 from him on the pretext that she was helping her brother in

Bullitt testified that the most damaging effect of her conduct was on their baby. Neither mother nor child was capable of staying with each other for any length of time without pushing themselves into a very nervous condition. Having left Louise at home one day, Bullitt testified he returned to find that his wife had put the whole household through a terrible experience (apparently due to her drinking and hostility).

On their return to

Bullitt said he came to

Although the parties apparently never discussed any agreement about a separation or divorce, they finally separated in November, 1929.

Four witnesses were called by Mr. Bullitt: Ferdinand Hommet (chauffeur), Alfred Mijon (butler), Louise Mijon (cook), and Hortense DeJean. All four confirmed Bullitt's testimony about Louise's continuous drinking, her disrespect for him, the damaging impact on the child, and her association with Miss LeGalliene.

Bullitt was granted custody of their daughter Anne. He agreed to provide support funds for Louise during her lifetime.

Her secret marriage to

‘TO ME DEATH MEANS PEACE’

Nineteen-thirty! The great Depression! Climbing unemployment statistics. Lengthening breadlines. . . President Herbert

Hoover, as have all presidents, had pledged "to end poverty in

Then Herbert

Hoover, whom Louise's brother, Floyd, had accompanied on his mission of mercy

to help feed starving Europeans, found himself faced with the problem of

feeding his own starving countrymen.

Jobless Americans were selling apples on street corners; homeless

Americans were building shelters out of cardboard and other scraps in colonies

they called Hoovervilles: and in the

It was another

troubled, turbulent period in American history.

But this time no one could blame the anarchists, communists, socialists

or agitators. Capitalism found itself on

the brink of collapse, without anyone who could really be blamed. It brought in its wake a revolution - through

the democratic process, however, with the election of Franklin Roosevelt as

President, and social legislation that changed the face of

Louise, who, as a socialist, used to argue that revolutions - where only the leaders are changed - do nothing to remove the causes for future depressions and wars, was by this time in no shape to argue with anyone about anything.

Bullitt had

made provision for her support, but his attorneys doled out the money in a way

that would hopefully keep her from using it for liquor and drugs. It was "prohibition time" in

When she and

Bullitt separated, she moved into her and Jack's old apartment on

One of the Villagers, Mary Ellen Boyden, who found Louise in a speakeasy, reported: "She was drunk and had a black eye," "I took her to her apartment. She could talk about nothing else except how she had loved John Reed."

She began to depend more and more on drugs to escape reality. Art Young, the cartoonist who was by then in his middle sixties, wrote: "Poor, poor Louise, she is heading toward suicide along the dreadful road of drugs."

Schizophrenia

and paranoia made reality merge with fantasy.

Incidents in the life of Jack Reed became twisted versions of her own

childhood. The great estate of his

wealthy grandparents overlooking

During

"normal" days she spent many hours in the library. Here bitter-sweet memories surfaced as she

leafed through Ibsen, Shaw and Sheridan.

But when she attempted to talk with others about her reading,

schizophrenia often intruded and listeners would sometimes be startled to

discover she had changed the subject in the middle of a sentence without them

being aware of it: "I think the

social changes in

She became an embarrassment to her friends who began to avoid her. Any suggestion that she take hold of herself, perhaps enter a sanatorium, infuriated her and sent her home to brood in her imaginary world where her critics were vanquished easily by her sound reasoning.

She moved to

She wanted Louise to write the book about John, and enthusiastically began collecting material, shedding tears as she found herself looking at pictures of him and her other son, Harry, while they were children on her parents' Cedar Hill estate, and reading again his early poems and affectionate letters home.

As the days passed, Mrs. Reed

began to notice an alarming change in Louise's "Dear Muz"

letters. She had known nothing about her

daughter-in-law's problems, and had no way of knowing that the letters were a

clear indication that Louise's schizophrenia and paranoia were deepening. She was bewildered and puzzled and wrote

letters to

Interspersed would be rational letters. Mrs. Reed's confusion and bewilderment grew when Louise's letters suddenly began informing her that Bullitt had treated her shabbily, refusing to let her have their daughter Anne, or even to see her.

Mrs. Reed wrote:

. . .There are so many things I do not understand about your situation. You write as if you had no money except for what you earn. Surely you were provided for under the divorce, were you not? And about Anne? Does it mean they have taken her away from you? Your letters are dear, but so very vague.

I dare not write down my sense of outrage about the way Bill is behaving. It all seems so impossible - as if no person with any sanity at all could do these things. Where is Bill? How do they conceal that he is off his head?

. . .I thought you got alimony or a settlement, did you not? I still do not understand how they could take Anne away from you.

Sad, depressed and alarmed, Mrs. Reed wrote that she did

not think she would be able to raise the money for a trip to

Louise, however, kept doggedly at the task of trying to induce important people to help her with what she insisted would be a most important contribution to literature and history--the story of her life with John Reed. All found a way out of helping. Some said it brusquely, some gently, but it all came out NO.

One of the gentlest and most

sympathetic of Reed's friends was Bob Hallowell, the painter from

But, as the Reed biography by Hicks shows, she gave him little information about herself, and she continued making notes and plans for a book about her life with Reed until the day she died.

Americans who came to

Her letters during those two years - her last - ranged from complete clarity to incoherence. From the Hotel Raspail where she was now living, she wrote to Art Young:

I always

imagined that it was morbid to write a last will and testament but Bill got me

over that idea about eight years ago when we walked into the Gerard Trust Co.

in

Mine troubles me now for this reason: There is no use in fooling myself into believing that I am not in failing health. . . Don't think I am bitter or afraid to die. Ernest Dowson (Ernest Christopher Dowson, the nineteenth-century English lyric poet) wrote, "I am not sad but only tired of everything that I ever desired." I feel like that. To me death means peace. But I have in my unpaid studio letters, books, paintings given me by the most famous people of our time. I have my own books and manuscripts which I think Anne should have.

In this case I must make another will. It must be a will so that if I die here, or somewhere else, suddenly, someone will take charge of things here. Perhaps Bill will see that I get buried decently - also for the sake of Anne.

In sharp contrast was an almost illegible letter about Fred Boyd, a close friend of Reed's.

. . .He was a conceited little

cockney whom Jack picked up abroad to be

his secretary because Jack said he was a perfect machine. Boyd amused him because he had never touched

good wine. . .The last chapter of Boyd is this:

When he heard I was having difficulty with Bill, he hurried to him to

offer his services (for a certain sum, of course). He told Bill that I had lived with Reed

before marriage, which he already knew.

And since I had done the same with Bill it was entirely silly. Then he started on a series of fantastic lies

such as that I was a descendant of Benedict Arnold whereas it was Aaron

Burr. A year later I saw Bill in

Her statements

and exaggerations grew more fantastic. The strangest was a revelation to Reed's

friends - assertion that John Reed was in reality an agent of the American

government in

Her restless

sleep became a series of nightmares. She

was in

One night she awoke sobbing and, rushing to the window, leaped outside. She was taken to the hospital but was forced to leave before her foot was completely healed because of lack of funds. One who heard of her financial plight was Raymond Robbins. He sent her five hundred dollars. "He is so rich," wrote Louise, "when I started paying him back, he cried."

She began

going downhill faster and faster.

Fantasy became more dominant than reality. A month before she died, Louise wrote from

. . .Maybe I feel like Benjamin Franklin or dear Thomas Paine wandering these streets these days with war clouds floating over us which none of us accept. Sometimes I think of the promise I made to Jack when he was dying not to do away with myself. So now I go armed. No more broken feet. No more hospitals without good reason.

And only a week before she died after collapsing while walking up the stairs to her room at the Hotel Raspail, he received a postcard from Louise. It was from 50 Rue Vavin where she had rented a small studio.

I suppose in the end life gets all of us. It nearly has got me now - getting myself and my friends out of jail - living under curious conditions – but never minding much. Know always that I send my love to you across the stars. If you get there before I do - or later - tell Jack Reed I love him.

THE END

EPILOGUE

It was a simple graveside

Protestant funeral service. A cold

drizzle fell on the casket and the dozen or so people surrounding the

grave. There was a minister, a handful

of the tenants who lived in the small

The minister was from the church

that catered to the spiritual needs of those Americans living in

From his prayer book, protected from the rain by his umbrella, the minister read a verse from the Psalms, another from Isaiah, and then, since he had been told very little about the deceased, he spoke briefly about the uncertainty and impermanence of mortal life. During the benediction, the mourners, mostly Catholics and understanding little of what the minister had said in English, crossed themselves and all followed the minister to the cemetery gates. Two laborers, who had been leaning nearby on their shovels, finished filling and smoothing the grave and, after erecting a temporary marker, they also left.

There were no flowers and no messages of condolence. Louise Bryant died alone and forgotten.

The many who knew her when she was involved in historically significant events, did not learn about her death until four days later, when a brief Associated Press dispatch reported it in the newspapers.

Miss Bryant, a native of

The death of the well-known

communist, who made a reputation as a journalist in

The item's skimpiness must

surely have been written the way Ambassador Bullitt wanted it written - without

identifying him beyond his name and saying as little as possible about his ties

to Louise Bryant, the mother of Bullitt's only child, who had been living as a

recluse in

Ironically, at the time Louise

died, Bullitt was in the headlines with the news that he had given up his post

in

The year 1936 also

saw her brother, Floyd Sherman Bryant, the Rhodes Scholar and associate of

Herbert Hoover in European famine relief work, become manager of exploration

for the Standard Oil of California. Four

years later he was elected to the Board of Directors, and in 1942 he became a

vice-president of the giant oil corporation.

In 1956, the brother of Louise Bryant, who took the radical road to a

lonely death, became an Assistant to the Secretary of Defense. He died in 1965 while visiting a daughter in

The few still

alive in the seventies who recalled Louise's mother, remembered her as a lady

who was always timid, gentle and devoted to her family. When she died on May 4, 1924, the weekly

Tribune-Register of

Sheridan

Bryant, the Southern Pacific Railroad conductor, who occasionally allowed

Louise to sit in the caboose cupola of freight trains as they slowly struggled

up grades through the magnificent mountains dividing

Permanently

war-crippled Bill Bryant, who died in 1944, was buried in the

Eugene O'Neill's reaction to the news of Louise's death was reported to have been one of shock. Lincoln Steffens, who was 70 and near death, was similarly affected. He passed away that fall. Contacted by the New York Times, Ella Winter recalled, among other things, that Louise was "the pregnantest woman" she ever saw.

In

The Oregonian,

in turn, carried a story about the days when radicals marched through the

streets of

Commented Mrs. C. H. Crichton, an aunt of Paul Trullinger, in 1972: "We were all shocked when Paul married her. Today I think all that was wrong with Louise, was that she was born many years ahead of her time."

Several former

women friends of Reed issued disparaging statements. For instance, Nina Faubion, the daughter of

"However," commented reporter Hughes at the end of the

article, "it was Louise, who was at Jack's side when he died of typhus in

the

Unfortunately, everything that has been written about her in the four decades since her death is based mostly on the years that began in the fall of 1915 when she met John Reed, until his death in 1920. She has thus been described - out of context of her entire life - as a self-aggrandizer, an opportunist, pretentious and a below-average writer.

Her death did

not even create the furor John Reed's did with reports he had expressed regret

and sorrow over his role in the Bolshevik takeover of

Reed's repentance is based on what three American radicals had to say. They were: Emma Goldman, the anarchist who took care of dying Reed until Louise arrived in Moscow; Ben Gitlow, a one-time candidate for Vice-President of the United States on the communist ticket, and Anna Louise Strong, the Seattle schoolteacher, an activist during the Pacific Northwest Wobbly crisis in the first and second decade of this century.

All three were

dedicated socialists and enthusiastic supporters of Lenin's campaign to replace

capitalism in

What appalled and horrified the Goldman-Gitlow-Strong trio was the ruthless suppression of all dissent and opposition, especially the murderous purge of many who had played an important part in bringing the new regime into existence.

Among the many others who were disillusioned for the same reason was an unusual woman named Angelica Balabanova, and it was she who wrote about Louise's repentance.

Angelica was

one of the many young people in

Angelica left

her home in the Ukrainian part of

Angelica was

among the first Russians to become a close friend of both Louise and John Reed

when they arrived in

Angelica and

Louise met in

"As soon

as Louise returned to

"'Oh, Angelica,' she would say in these moments of lucidity and confidence, 'don't leave me, I feel so lonely. Why did I have to lose Jack? Why did we both have to lose our faith?' Shortly after this I heard of her death."

Poor, poor Louise! She was also by this time telling Reed's friends that Jack was really an agent for the United States government in Russia, and how she fought off attempts by Bill Bullitt to strangle her.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First thing

one discovers undertaking research, is that people who select library work for

a career, have one thing in common - they love books and the contents of books

and are eager to share their knowledge with others. Everywhere, from the elaborate libraries on

the

This is not to underestimate the contributions of the many others who helped, some becoming almost as enthusiastically involved in locating material for reconstructing the life of Louise Bryant as was the author, himself.

We therefore wish to acknowledge gratefully the help received from library personnel, in addition to those already mentioned, as follows: The University of Washington and City of Seattle; the Tacoma Public Library and University of Puget Sound; The State of Washington Library in Olympia; Portland-Multnomah Library; Marysville, California Library; California State and Sacramento City Libraries; San Francisco City Library; Ventura and Santa Barbara, California Libraries; Los Angeles City Library; Libraries in Syracuse, New York and Chicago; University of Nevada and University of Oregon Libraries, Olympia and Lacey Libraries in Washington state, and personnel in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Others who provided valuable help included:

The American Pro Cathedral

Church of the Holy Trinity in Paris; The Episcopal Dioceses of San Francisco

and Reno, Nevada; Dr. Martin Schmitt, University of Oregon curator; the late

John Reddy of Reader's Digest; Kendra Morberg, Mrs. Gladys McKenzie Hug and

Mrs. Keith Powell, Louise's fellow students at University of Oregon; Miriam Van

Waters, Framingham, Massachusetts, University of Oregon campus magazine editor;

Carl R. White, Island I County, Washington school superintendent; Mrs. C. D.

Crichton of Portland, cousin of Paul Trullinger; Wallie Warren of Reno; John

Reed of Washington D. C. (Jack's nephew); Arthur Spencer of the Oregon Historical

Society; L. S. Geraldson of Auburn, California; Philip Earl of Nevada

Historical Society; personnel in vital statistics department at Sacramento;

Senator Frank Church of Idaho; Public Relations Department, Standard Oil

Company of California; Kylie Masterson of North Hollywood, California; Paul 0.

Anderson and Robert Merry pf the

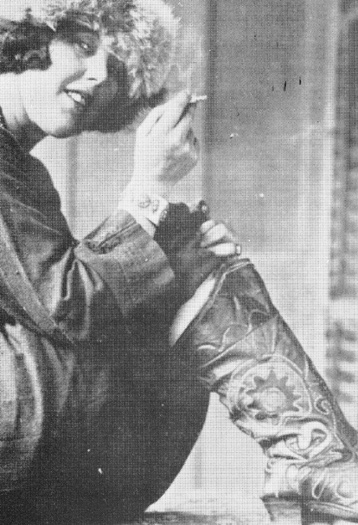

The Cossack costume was a gift from a wealthy Russian woman whom Louise interviewed. She was far less concerned, said Louise, about the property she was about to lose than she was about what the Revolution was doing to the servants. They were leaving her, and those who stayed insisted on calling her “tovarishcha”, comrade.