PART TWO

UTOPIA MUST WAIT

It was her second outbound trip over the Atlantic for Europe in less than three months. The German U-Boats were more menacing, for now that the United States was formally at war, everything afloat from an American port was considered a carrier of troops or munitions, no matter what national flag a vessel flew.

But this time Louise was not alone. Jack was along to share her excitement, and the certainty that they would be witnessing tremendously-significant events, and she would, at last, achieve her goal of becoming an important journalist, while Jack would perhaps be able to regain his lost prestige as a great writer.

As accredited journalists they had a first class cabin, but as soon as they learned that the boat's steerage section was full of people who had once left Russia, and now that the hated czar was gone, were returning, they lost no time in joining them.

They spent all their time with these people who had come abroad with all their possessions in gunnysacks and parcels. These were some of "the huddled masses yearning to breathe free," of Emma Lazarus's moving prose engraved on the Statue of Liberty, Jack told her. They had fled Czarist Russia only a decade or two earlier to avoid compulsory military service, to avoid being sent to Siberia for raising their voices in protest, or to avoid perishing in police-encouraged pogroms against Jews.

A Utopian America had beckoned them then, and now that the despot Nicholas II was gone, Russia beckoned as brightly. Russia, without a czar, promised an escape from American sweatshops, vermin-ridden tenements, and for Jews, an escape from the odious name "sheeny." Louise was deeply moved and wrote about the people who were risking their lives to return to their homeland.

Hunted, beaten, mistreated before they fled to America, they had somehow maintained the greatest love for the land of their birth. . . It was along way back for these people. We were held up a week in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on their account, while officers came aboard every morning and examined and reexamined them. Pitiful incidents occurred. There was an old woman who clung frantically to some letters from a dead son. She secreted them in all sorts of strange places and brought down suspicion upon herself. There was a youth they decided to detain - he threw himself on the deck face down and sobbed like a child. They were all in a state of nervous terror.

(Louise and Jack appear to have agreed to completely separate their personal lives from the material intended for publication. Thus Reed’s name appears only once in her “Six Red Months in Russia.” In the original edition she dedicates the book “affectionately to that beloved vagabond, John Reed, and Reed, in his “Ten Days That Shook The World,” refers to her only twice: When discussing the the charges of atrocities involving raping of members of the Women’s Death Battalion, he points out that Louise Bryant has interesting material in her book about the women-soldiers, and again when she barely escaped death during a deadly attack on Red Guards. Nowhere is there any suggestion tht they were husband and wife, or even that they had come to Russia together. Interestingly, and probably also the result of an agreement, her book opens with the simple statement, “When the news of the Russian revolution flared across the front pages of all the newspapers in the world, I made up my mind to go to Russia. Early in August I left America on the Danish Steamer, ‘United States.’”)

The first thing Jack told her when they came aboard, wrote Louise in her notes, was that he had no intention of honoring his promise to the State Department, and that he would, in fact, attend the conference of socialists from all over the world when they met in Stockholm. Not only that, but he was carrying greetings and other material from American comrades to the meeting. He did not feel, said Louise, that a government, which could not exist without constantly practicing deception at home and intrigue abroad, had a right to exact any such pledge from one who was able to trace his ancestry to Patrick Henry.

When the British soldiers came to their cabin to double check their passports and perhaps search their room. Jack was ready for them. He had carefully hidden the material under the carpet, and, said Louise, two bottles of scotch and some glasses were sitting out invitingly. "They toasted King George, President Wilson and President Poincare of France. Then one of the marines remembered that Italy was also on their side, but nobody knew the name of their president, or even if they had one. So they toasted Italy anyhow. By that time they had forgotten why they came and when they left the one who was in charge, bowed and winked at me as be backed out of the door."

Counting the week the ship was delayed at Halifax, it took the S.S. United States three weeks to reach Kristiania (now Oslo) in Norway. At Kristiania they boarded a train for the trip across Norway, then north along the coast of Sweden and into Finland. The endless evergreen forests rushing by their train windows were so like the forests of Oregon and Washington on the West Coast, Louise could have been traveling from Portland to Seattle, were it not for the Scandinavian faces she saw on station platforms and all about her.

On the train she had her first encounter with a lesbian. The train was crowded, as were all trains in those hectic, feverish days of war and revolution. They had become friendly with a Czarist courier returning home to an uncertain fate. "The only way we could get some rest was to take turns and sleep a little while on a bench in a compartment," said she. "Jack and the courier would stand outside while I shared a bench with a woman passenger. Then they would take their turn and we would stay in the corridor." Louise stretched out on the long bench in the compartment, her feet touching those of the Norwegian girl sharing the bench with her.

She awakened with a start, and it was a moment before she realized she was not dreaming - someone was fondling her face, and a hand was pressing her thigh. It was a woman - the Norwegian girl. "What are you doing," screamed Louise. Then she kicked at her and ran outside, shouting to Jack and the courier. "What is that woman in there trying to do to me?" When she told them what had happened, both of them - to her great amazement - roared with laughter. Then Reed looked at her in the dim light of the corridor and said: "Honey, that girl is a lesbian. Have you never heard of a lesbian?"

"Yes, of course I have, but I thought, I thought. . . Oh, my God. . ." The next day, said Louise, traveling through Norway, the girl sat gloomily looking out of the window without once glancing in their direction.

Louise caught her first glimpse of the soldiers of the new Russian revolutionary army at Tornio, a tiny town in Finland, just across the border from an equally tiny Swedish town called Haparanda. Finland still belonged to Russia then. The date was September 10, 1917. "It was a cheerless, gray morning," she wrote. "A steady drizzle added to the mournfulness of everything about the cluttered little station. The soldiers of the revolution - great, blond giants, mostly workers and peasants, wore old dirt-colored uniforms from which everything that had to do with czardom had been removed. They carried ugly-looking bayonets and called everyone by such endearing customary Russian names as 'little grandfather,' 'little mother' and 'precious one.'"

Thus she described her first impression of the new Russia. And then came the bitter disappointment of those who had been dreaming they were returning to a land where the czar had been banished - and with him war and hunger and want - and that the cry "svoboda" (freedom) was being shouted from the rooftops.

"A tall, white-bearded patriarch, returning after a thirty-six year exile, was beside himself with excitement. He rushed from one soldier to another. 'How are you my dears? What town are you from? Ah, I am so happy to be here again. . Do you know where Nikolayev is?' The soldiers kept smiling indulgently, but finally one spoke sternly to the old man: 'Listen, little grandfather, there is no time for reunions.' The old man clutched the soldier's arm. 'What are you trying to tell me? Is Russia not free? What is there to look forward to now but to happiness and peace?' 'There is fighting and dying ahead, little grandfather; our land is full of traitors within and enemies without.' The poor old man collapsed. His dream of Utopia was shattered."

There was more, a good deal more. One woman was hustled back across the border into Sweden because her papers were not in order, while her eighteen-year-old son was ordered to stay. She screamed and pleaded and said she was born in Russia and knew nothing about papers and visas, but it was of no avail; she was carried across the border screaming and cursing. The courier himself was questioned closely, his fate still uncertain.

Tornio reflected the confusion that prevailed all over Russia. There were fantastic rumors and reports. Each time the train stopped at a station and the passengers got off to stretch their cramped limbs and get hot water for the tea they constantly drank while traveling, the rumors and reports grew more and more frightening, and more bizarre. They were not altogether new to Louise. She had read them in the English language papers in Paris when she was there, and the New York papers ware full of rumors of atrocities, often presented in such a way as to make them sound like news.

But here, in a wartime atmosphere, they sounded ominous and dangerously near. There were rumors that women had been mass-raped; rumors that at one place in Russian Asia, unmarried women had been nationalized the way everything else had been by the Bolsheviki; rumors that Kerensky had been assassinated; and rumors that Lenin had left his hiding place in Finland and was back in Petrograd ready to take over from the Provisional Government.

Because it was near the Swedish border, from where messages could be sent in code, Tornio was full of spies and secret agents, most of them British or French. One Briton, his curiosity aroused by the sight of this handsome young pair of Americans waiting their turn to be examined before being permitted to enter Russia, managed to get them involved in conversation.

"But this is unbelievable. You're not planning to take HER into that bloody country?"

"Why, of course," Reed told him, "Why not? She's my wife and she wants to see for herself what is happening in that bloody country."

Louise gave the Briton one of her most radiant smiles: "Yes, why not? You know I may never again get a chance to see a real revolution."

The Briton muttered a godspeed, shook his head and Left them.

At Tornio Louise also got her first taste of the disorder and chaos that is an inevitable part of a revolution. Before they were allowed to board the train for the capital, they had their passports and correspondent credentials examined again and again by men who appeared to be uncertain about what they were supposed to do. Their baggage was also examined over and over again and most personal items like Louise's few cosmetics and even more personal things were confiscated. Then, guarded by six bayonet-wielding soldiers, she was marched off to a shack where she found herself before a chunky Russian girl with bobbed hair and wearing soldier’s boots, who ordered her to undress. It was dreadfully cold and Louise reluctantly took her clothes off - then the girl, without glancing at her - told her to put her clothes on again. Naked, her teeth chattering, her clothes about her on the floor, Louise demanded to know why, she,an American citizen, was required to dress and undress without being searched. The Russian girl Looked at Louise and said: "Chortznayet (the devil knows); all women have to do it when they come in here."

Outside the shack, Louise found Reed talking with a soldier. His face was clouded. "I want to show you something," he said, "It has just been posted." On the railroad station wall was an announcement in both Russian and French. It was dated two days earlier, September 3, and announced the declaration of martial law by Premier Kerensky:

"... General Kornilov dispatched to me. . .a demand to give him supreme military and civil power, saying that he will form a new government to rule the country.. the Provisional Government considered it necessary, for the salvation of the country, to take all measures to secure order and suppress all efforts to usurp the supreme power won by our citizens in the Revolution. . .The city of Petrograd and the Petrograd district are hereby declared under martial law by action of this telegram. . . I appeal to all to accomplish their duties in defending the nation.

(signed)

Premier Kerensky

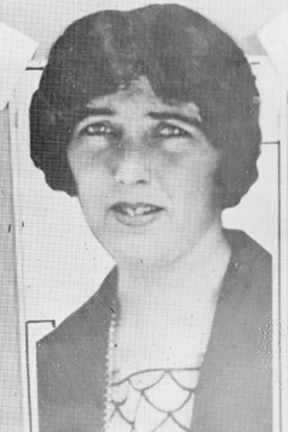

This is the picture Alexander Kerensky gave Louise when she and Reed interviewed him. He was still head of the revolutionary government but not too long after the interview he barely escaped to England as Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov, better known as Nicolai Lenin, took control of Russia.

It was an unusual interview, to say the least, details of which Greene found in Louise’s notes. Kerensky was lying on his side on a couch in great pain because of a severe kidney ailment, and apologized for greeting them in that condition. Reed, of course, knew all about kidney ailments. Indeed, it was while he was in Johns Hopkins Hospital for kidney surgery a year earlier that O’Neill moved in with Louise in their apartment.

So there they were, reveals Louise, comparing notes on the respective kidney ailments, before turning to discussing Kerensky’s rapidly vanishing hopes for continuing the against Germany with the Allies and bring Socialism to Russia by democratic means, in the face of Lenin’s irresistible appeal to soldiers, workers and peasants with the cry: “End the war, take the factories and the land, we will make legal in due time.”

At the many stations where their Petrograd-bound train stopped, they heard more and more fantastic rumors and reports. "The scraps of conversation we caught sent shivers over us," wrote Louise. "On one station platform, a pale, slight young man, standing beside me, suddenly blurted out: 'It was terrible ...I heard them screaming.' Heard whom? Heard whom? I asked anxiously. 'The officers! The bright, pretty officers,' replied the young man in a whisper. 'They stamped on their faces with heavy boots, dragged them through the mud and threw them in the canal.... They killed fifty and I heard their screams.'"

In her first by-line dispatch from Russia, Louise said: "I have arrived on the crest of a counter-revolution. The rumors are flying. Petrograd is in a stage of siege. Trenches are being dug outside the city. What has happened since then? We walked up and down the station platform under heavy guard, feeling Like prisoners."

They stood on the sidewalk in front of the Petrograd station, Reed wondering how they could get to the Angleterre Hotel where he had stayed with Boardman Robinson in 1915. Then a young soldier, seeing a handsome American with a pretty woman, their baggage on the sidewalk, approached and asked: "Aftomobil, da?" "Da, spasibo," said Reed in his limited Russian.

(Neither Louise nor Jack were linguists. Louise had studied French at both the University of Nevada and the University of Oregon, and Jack had picked up enough Russian on his former trip to get by. Fortunately, most literate Russians could speak French well, and some could also speak English. In addition, by the time they arrived in Petrograd there were hundreds of Americans there ahead of them. Most of these were radicals who had fled Russia a decade or so earlier to keep from being sent to Siberia for their activities, and now that the czar was gone, had returned to the place of their birth. Hundreds of others, notably Jews, were returning as had those aboard the ship on which Louise and Jack had made the trip, and all were eager to be seen with and help this important American couple as a means of gaining favor for themselves in the new regime.)

As they whirled away from the noisy station, they were startled by the stillness of the city, the absence of anyone anywhere except sentries. "We were prepared for anything cut this," wrote Louise. The "aftomobil" crossed a curving bridge into the main part of the city and here too, nothing seemed to move. The young soldier, bubbling with enthusiasm, explained the stillness. The Kornilov counter-revolution was over and the city was back to normal, which was anything but the way Reed recalled it during the early morning czarist hours of 1915.

They were challenged by sentries now and then, but the soldier yelled something and without slowing roared on. As the car stopped and they started for the hotel entrance, a strange thing suddenly happened - one of the many that never failed to surprise her when she was in Russia. "Mysteriously, out of the darkness," wrote Louise, "the bells in all the churches began to boom over the -sleeping city, a sort of wild barbaric tango." They could find no one, not even Jack's friend Bill Shatov was able to explain why the bells in all the churches should have suddenly broken the night stillness as they did at that particular moment.

At the Angleterre, the porter, annoyed at being awakened when it was not yet four in the morning, showed them their room on the third floor. It was a huge, vaulted room all gold and mahogany, with old, blue draperies. Most of the furniture was shrouded in white coverings. In one corner was a huge bed and beyond that was an enormous bathtub cut out of solid granite. Light was provided by a dazzling old-fashioned crystal candelabra. "Only twenty-five rubles," said the porter. It was bitterly cold in the room, and when Louise pulled back the drapes, she saw why. The windows had been smashed by gunfire during the riots and hadn't been replaced. Above the huge bed was a sign which declared that the speaking of German was strictly forbidden.

Clinging to Reed for warmth, it seemed to Louise that she had only just shut her eyes when there was a loud pounding on the door and, before either of them could answer, the door opened violently and a burly blond Russian entered and demanded to know what they wanted done about their baggage. It was a while before they realized he was talking German. Reed pointed to the sign above the bed. The Russian looked puzzled, and then said in German: "We are not at war with the German language, only the Germans." Russians, Louise soon learned, paid little attention to the signs, not even the ones on each table in restaurants: "Just because a man must make his living by being a waiter, do not insult him by offering him tips."

"Why is he so blond?" Louise asked when the Russian porter was out of the room. Reed grinned, and Louise knew the answer would be amusing but not very informative. "Because," said Reed, "He is a White Russian, and not the kind that live on the East Side in New York. White Russians are always blond, that's why." Louise laughed and kissed him.

In the morning she yawned and said: "Let's not get up today, it's so terribly cold." Reed pushed her gently away from him. "There's a revolution outside, Mrs. R," and getting out of bed, Reed began to dress. Louise sighed and followed him, her teeth chattering and her breath turning to vapor.

Louise could hardly contain her excitement at her first daylight sight of the magnificent city then called Petrograd. Peter the Great began building it on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland in 1703. He wanted to build a city that he could call "The Window of Europe," and to do this he brought together Europe's greatest designers, architects, painters, artisans, and ordered thousands of serfs brought from all over Russia to the cold swampy Neva Delta to do the building. Few of the laborers survived the climate and working conditions.

Louise wrote in her first dispatch from the Russian capital:

Petrograd is impressive, vast and solid. New York's high buildings have a sort of tall flimsiness about them that is not sinister; Petrograd looks as if it was built by a giant who had no regard for human life. The rugged strength of Peter the Great is in all the broad streets, the mighty open spaces, the great canals curving through the city, and rows and rows of palaces and the immense facades of government buildings. Even such exquisite bits of architecture as the graceful old spires of the old Admiralty building and the round, blue-green domes of the Turquoise Mosque cannot break the heaviness.

Built by the cruel willfulness of an autocrat, who had named it St. Petersburg, after himself, more than two centuries ago, this mighty city, by a peculiar irony. . . has become "Red" Petrograd.

INGREDIENTS FOR A REVOLUTION

Russia is a land of superlatives. Its eight and a half million square miles cover more than one-half of Europe and a third of Asia - a full sixth of the earth's surface. Only China and India have larger populations. There are 150 nationalities and tribes. There are white people and yellow-skinned Mongols. The whites range from flaxen haired Russians and Estonians in north European Russia, to dark, fierce-looking people in the south and southeastern parts. In the Caucasus there are even descendents of the Negro slaves brought from Africa when Czar Alexander II started freeing Russian serfs. To cross Russia from one end to the other means crossing eleven of the earth's twenty-four time zones. In the extreme north, the cold is so intense that mercury in ordinary thermometers freezes, while in the Kar Kum Desert of Russian Asia, it's so hot one doesn't dare touch anything with bare hands.

It has fantastic mountains, mighty rivers, every imaginable natural resource to sustain life, and is so vast that as late as the 1930's Russian scientists were finding tribes in some of Russia's remote areas living as man did a dozen or more centuries ago.

Russia was always a land of glittering palaces, magnificent cities, splendid museums, and the world's most ornate cathedrals. It could boast of having given the world giants in literature, music, dancing and painting. But, at the same time, it was a land of tyrannical rulers, incredible poverty, the world's worst slums, the most superstition-ridden priests, the highest illiteracy and infant mortality rates, the deadliest "pogroms" in which thousands of Jews perished, the most ruthless repression, and what all of these inevitably add up to - riots and revolution. Neither long prison terms, banishment for life to Siberian camps, nor the most primitive forms of torture could stop Russia's periodic revolutionary upheavals. These were sometimes fomented by land owners, sometimes by the nobility, sometimes by underground socialist workers groups, and sometimes by Russian Intellectuals, as was, for example, the insurrection of December 26, 1825, in which Aleksandr Pushkin, the poet, was involved and miraculously escaped punishment.

World revulsion against what was happening inside Russia did not materialize, however, until "Bloody Sunday" - January 22, 1905. On that day, thousands of men, women and children, many of them families of workers involved in long strikes, appeared before the Czar's Winter Palace in what was then still St. Petersburg. They came there to petition the czar for reforms. Ironically, they were not led by revolutionary agitators, but by a priest named Father Georgi Gapon, who had organized a workers' movement with the help of the czar's own secret police, in the hope of countering the revolutionary socialism that had begun to grip the country.

The troops of a panicky Czar Nicholas replied by opening fire and more than one thousand men, women and children were killed.

This was followed by such world-wide revulsion and chaos and revolution inside Russia, that the czar agreed to bring something new into Russian political life - the Duma, a mild version of the British parliament and, at the same time, agreed to freedom of public expression of grievances. The second was a hoax - it gave the czar's secret police a chance to find out who the troublemakers were. The Duma concession was an equally useless gesture. The czar retained the power to dismiss a Duma if he disapproved its work, and even arrest the elected members. He dismissed the first, second and third Dumas, and at the time that Jack and Louise were there, the fourth was in session.

The czar's concession ended, at least temporarily, internal Russian turmoil and violence. But the restiveness triggered by the humiliating Russian defeat in the Russo-Japanese war continued to smolder. It was, indeed, an element in creating the conditions that, among other things, brought on the strikes and the march on the winter Palace and the czar's panicky reaction.

By "bloody Sunday", also, Lenin, whose real name was Vladimir Ilich Uylanov, had become an element in the events that were racing toward a disastrous end for both the czar and capitalism in Russia.

Louise found her background and the prior events in her life helped her while trying to sort out the chaos that was Russia in 1917 - Wadsworth and Eugene Debs, Reed's reports on his life in Mexico with Pancho Villa and his peasant rebels, the Ludlow massacre. Professor Howe at the University of Oregon, the horror stories of confrontations of the radical Wobblies (Industrial Workers of the World) with police in Oregon and Washington state.

Moreover, the Russian capital was full of Americans who had fled Russia a decade before - many of them well-informed on Russian history and the radical underground - and had now returned to the land of their birth before she, Jack and their steerage companions arrived. These people were not only happy to act as interpreters, but also to provide helpful information about what had happened to bring on the Czar's collapse and the significant events that followed. Among these were Bill Shatov and flaming red-haired wife, Anna, both of whom Reed met and knew well in New York. Louise soon became aware that Bill Shatov's interest in her was inspired by something more than a desire to see she was well informed on revolutionary developments. Sharp-eyed Anna, however, saw to it that opportunities for interludes of any sort did not present themselves, while war and revolution raged everywhere in Europe.

There were a good many others there, some of whom Louise had met in Greenwich Village, and they were all eager to help these prominent American journalists. The Russians themselves, at each other's throats over the form the revolution should take, had one important thing in common: All eagerly wanted their side "correctly" presented to the American public.

All of them, recently returned Americans and Russians alike, found pleasure in talking with Louise. She listened intently, even though a great deal of what she heard was not new to her.

They were drinking tea from cups in which floated almost razor-thin slices of lemon. Louise gave up trying to' drink hers as she had seen an elderly man on the train do - straining the tea through a small lump of sugar gripped between the teeth. Bill Shatov was explaining that what had happened in March which brought on the abdication of Czar Nicholas was not really a revolution. "You might say it was a revolution by default," he said. "There was no planning or plotting. Everything fell apart and there it was. The czar quit and the power to run the country was anybody's for the asking." And to Louise: "Here, let me show you how to drink that. What you do is you take a sip of tea and then a small bite of sugar."

Of all the czars and emperors the Russians ever had, none was as inept arid as autocratic, said Shatov, as was the last of the Romanovs, Nicholas II. He had a deep feeling of inferiority, which he attempted to overcome by bluster and decisions without thought of consequences. The need to cover indecisiveness with a mask of self-confident resolution caused him, among other things, to depend oh advisors who, like himself, lacked the ability to grasp the deep significance of the many problems that Russia faced during the 23 years he ruled Russia. His wife, Alexandra, did little to endear him to the Russian people, especially during the war years when Russia was fighting Germany. Alexandra was born in Germany, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria of England.

The lives of Nicholas and Alexandra were complicated by the many attempts made on his life and the tragedy of their son, young Alexis, a victim of hemophilia, a rare disease in which the blood has difficulty coagulating. This caused both of them, in their desperate attempts to save the boy, to depend on quacks and scoundrels who called themselves mystics. And of these, none was a greater charlatan than one Siberian mystic who played a significant part in bringing about their downfall. His name was Gregor Efimovich Rasputin, a name that suited him like a glove. The Russian word "rasput'nyik" means one who is dissolute, lewd, vicious and shameless.

Born in the Siberian town of Tobolsk, he abandoned his wife and three children to become a wandering religious mystic and faith healer. He soon developed a reputation among superstitious peasants that he had divine powers to perform miracles in healing. Rasputin's contribution to the art of reasoning was in providing a unique definition of the word "sin" to justify his unorthodox behavior. Sin, said he, is an offensive action committed by an individual who is sinfully inclined. To suggest that he, Rasputin, (his real sur name, by the way, was Novykh) was sinfully-inclined, was a preposterous assumption, for how can one possess an inclination to be sinful and, at the same time, possess divine power to perform miracles in healing.

In 1907 he turned up in what was at that time still called St. Petersburg, and Czar Nicholas and Alexandra invited him to the palace to try his healing art on young Alexis. The boy's bleeding stopped. Whether the cure was of a permanent nature will never be known, for Alexis, along with his parents and four sisters were murdered by the Bolsheviki in July of 1918.

Nicholas and Alexandra were overjoyed and vowed eternal gratitude to Rasputin for the miracle he had performed on the heir to the Russian throne. Rasputin soon became a powerful element in the decision making process which affected the lives of Russia's millions.

Ultimately not only workers and peasants and merchants throughout the land, but also the nobility began to consider him a symbol of everything that was evil.

On the last day of December in 1916, he was lured to the palace of Prince Yussupov where he was murdered. The Czar and his wife then infuriated the destitute, the starving - everyone in Russia - by providing Rasputin with one of the most magnificent funerals ever staged in Russia.

It was the straw that broke the camel's back.

PRELUDE TO UPHEAVAL

By March of 1917, the Russians were in their fourth year of the war. Victories had been few and the suffering great. On the 22nd of March, food riots in Petrograd began to take on all the appearance of a spontaneous insurrection. Czar Nicholas, who had by that time made himself supreme commander of all of Russia's armed forces, ordered troops to shoot rioters, and looters. They refused. There followed complete anarchy. By March 25, the Czar was a virtual prisoner in his Winter Palace. On the 29th he announced his abdication, and with his abdication came an end to the rule of czars over Russia - the end of the three-hundred-year-old Romanov dynasty of czars.

With the Czar's abdication, the Fourth Duma asked one of its members, Prince Georgi Lvov, to organize Provisional Government. He did, and named Kerensky his Minister of Justice. In July of 1917, because nothing much had happened to alleviate the suffering of the Russian masses, a new crisis developed. Prince Lvov then resigned, and Kerensky became the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government.

By this time, Russia was in deep trouble. The workers, the peasants and the soldiers at the front had expected that with the end of the czar's rule there would be an end to the war; that great land reforms would be made and working conditions in the factories would be improved. The Provisional Government had promised to call a Constituent Assembly that would launch the program of improvement. Instead, the new government kept changing the date for calling the Assembly into session, with Kerensky insisting that Russia's first task was to help the Allies crush the Germans and then make domestic improvements.

(NOTE: Much of the background of the 1917 Revolution presented here does not come from traditional sources. It is based on information that developed during the author's conversations with an older brother, who was himself involved in some of the events that proceeded the Revolution, while the family was still living in Russia.)

Abhorring violence, the brother became an underground Social Democrat while still in his early teen years, and joined the ranks of those who believed - as did Karl Marx himself at one time - that socialism, under certain circumstances, might possibly be achieved by parliamentary means. He retained that belief until his death in Los Angeles at the age of 94, even though he was forced to flee Russia with the czar's police close on his heels. He had made the mistake of believing the czar's promises after "Bloody Sunday" and voiced an opinion about capitalism. He also provided details about Angleica Balabanova, whose role in the lives of Louise and Reed is discussed in the EPILOGUE. He knew her when both were children.)

Troops began deserting the trenches by the hundreds and then thousands. Peasants started looting the great estates, killing the wealthy owners and taking over the land. Above all the turmoil was the great cry of Lenin and his fellow insurrectionists who had returned from exile in Switzerland-"PEACE, LAND, BREAD. . .ALL POWER TO THE SOVIETS. . . .end the war and to hell with all capitalistic allies. . .take the land, we'll pass laws to make it all legal later. . .workers and peasants, stop producing for the profit of others, take and use that which you have produced!" That was the substance of Lenin's advice to the millions of hungry, war-weary Russian workers and peasants.

On July 15, 1917, new food riots broke out in the Russian capital, reminiscent of those that preceded the collapse of the czar's government about four months earlier. Lenin was not at all certain that the situation was, as yet, right for a revolution, but conditions were getting out of hand, and so he arc his fellow revolutionists decided to try and direct the riots into a full-blown revolution. They failed. Hundreds of Bolsheviki, including Trotsky and Stalin and Kamenev, who was Stalin's fellow-editor on Pravda, were imprisoned, and Lenin fled into hiding in Finland.

His full name was General Lvar Georgievich Kornilov. Son of a Cossack father, he had by 1917, established a distinguished record that dated back to the Russo-Japanese war. Shortly after the abortive July 18 insurrection and the jailing of the Bolsheviki leaders, Kerensky named Kornilov commander-in-chief of all Russian armed forces. Be medalled, a passionate disciplinarian, a long sword dangling at his left side and a tall Cossack hat on his head, Kornilov decided the first thing he must do was restore the death penalty to stop the headlong rush of deserters from the trenches. The feuding civilian Provisional Government refused him permission.

He decided that if Russia was to be saved, it must have a military dictatorship, with himself as dictator. A great many other generals and most upper-rank officers hailed his decision. When Kerensky received an ultimatum from Kornilov, he fired his. Kornilov refused to be fired and was soon marching on Petrograd with hundreds of Cossacks and other troops loyal to him. Word of Kornilov's ultimatum to Kerensky, it will be recalled, reached tiny Tornio on the border of Finland with Sweden, the day that Louise and Jack Seed set foot on Russian soil.

The Kornilov counter-revolution collapsed, but it was at this point, wrote Louise, that Kerensky made his great mistake in assuming that the real threat to his democratic form of socialism for Russia was in General Kornilov. Lenin was, after all, a socialist, a willful and misguided one to be sure, but still a socialist, thought Kerensky, and when it came time for manning barricades against reactionary forces he would surely be there. And so he made his fatal error: He called upon everyone, including the Bolsheviki, to defend Petrograd when Kornilov and his troops appeared on the outskirts of the city, and he freed from prison Trotsky and most of the other Bolsheviki who had been there since their arrest during the July attempt to overthrow the Provisional Government.

With all leading Kerensky opponents out of prison and Lenin's mighty cry. . ."PEACE...LAND...BREAD" on every available wall, said Louise, events began snowballing everywhere in Russia. In Poland, in White Russia, and other large sections of the country, the nationalists - mostly owners of property - were demanding autonomy and were refusing to obey orders from Kerensky's Provisional Government in Petrograd. The Finns declared themselves an independent state and demanded Petrograd withdraw Russian soldiers from Finland. Siberia and other large areas of Russia were talking about creating their own Constituent Assemblies and negotiating with the Germans for peace terms.

The desertion of soldiers increased at a terrifying rate. Most of the deserters wandered aimlessly about Russia, many returning to their villages to join in setting fire to large estates and murdering their owners. Moscow and Odessa were torn by strikes and transportation was paralyzed.

Trotsky was at the head of the most powerful of the soviets, the Soviet of Petrograd Workers. Rank and file soldiers of the huge 20,000-man Petrograd garrison had formed a revolutionary committee. Lenin was still in hiding in Finland. His wife, Nadyezhda Krypskaya (“Nadyezhda” means “Hope”), a revolutionary schoolteacher, brought messages and new propaganda leaflets to flood Petrograd. She was one of the very few who knew where he was hiding in Finland, and made nightly trips to see him and return while it was still dark.

While Trotsky was publicly denying planning an insurrection to take over the Provisional Government's power to control Russia, Lenin's message to his fellow-Bolsheviki made it clear that they might as well forget their cry, "All power to the Soviets," without an insurrection and violence.

The crisis kept deepening and finally came to a head with a call by Lenin's followers for a Petrograd convocation of an All-Russian Congress of Soviets for "the purpose of taking over the power to rule Russia. This was the showdown. Kerensky supporters were furious, outraged. They were going to stop the convocation, by violent means if necessary.

(The Russian word “soviet” means “council,” a group of people formed to act in the interest of others. In Russia, during the revolution that followed “Bloody Sunday” in 1905, and particularly after the czar’s abdication in 1917, they came to represent groups of workers, soldiers, peasants – everyone involved in the nation’s economic life. There were also “soviets” to represent villages, districts, towns, cities, provinces and so on. As such, the “soviets” represented the often-conflicting economic and political views of all segments of Russian society, except for priests, monks and employers of labor for profit. The various soviets from throughout the country were woven together into national federations somewhat in the manner of the individual local of the American Federation of Labor, and all of the soviets were bound together into an All-Russian Congress of Soviets.)

Following the call by the Lenin people to meet in Petrograd, a tremendous campaign got under way to influence elections of delegates throughout the country, with threats and predictions of disastrous consequences if Lenin's Bolsheviki took control, and, of course, promises of putting the revolution back on the track to achieve genuine socialism for Russia and a better life for all.

Louise, by the way, used the old Julian calendar dates - then still in effect in Russia. Thus, the call for the All Russian Congress of Soviets for November 7th is October 25th in all reports - 13 days before today's universally-used Gregorian calendar.

Who were all these men and women, many of whom Louise came to know and write about, and whose words and actions have so affected today's world? What did they want? What did they stand for? What did they achieve?

LENNIN: "RADISHES ARE RED ONLY OUTSIDE"

We don't want people," said Lenin, "who are revolutionists in their spare time. We want people who are willing to give all of their lives to revolution, We don't want people who suddenly find it convenient to become Reds. They are like radishes, red on the outside but always white inside."

Two years before "Bloody Sunday" of 1905, underground revolutionary leaders from inside Russia, and those who managed to escape or were exiled, met for two important conferences - one in London and the other in Brussels, Belgium.

All of them called themselves Social Democrats. They were, however, divided into two groups with radically divergent views on how best to achieve the goal of replacing capitalism in Russia with socialism. The purpose of the conference was to reconcile the views and form a united front.

Lenin had one plan for achieving the goal, and had not the slightest intention of reconciling it or moderating it or qualifying his readiness to give his life in order to achieve it. Julius Martov and Grigori Plekhanov, who represented the other view, were equally adamant. The conflict was irreconcilable, but not hard to understand.

MARTOV-PLSKJLAKOV: The revolution we're talking about has no precedent in history. It is not a political revolution in which only the people who govern are replaced. It is the world's first social revolution in which the factories, the mines, the forests, the railroads - the facilities for the production and distribution of everything necessary for the survival of a people, will be taken away from their private owners and become socially-owned. Our millions of landless peasants and most of our workers, with a rate of illiteracy unequalled in any civilized land, their minds drugged by ignorant, superstitious priests, are utterly unequipped to participate in a revolution aimed at replacing capitalism with socialism. They know nothing of socialism. The dream of every landless peasant is to change his status from being landless to landowner. . .the dream of every serf, freed only four decades ago, and now the owner of several tiny scattered strips of Land, is to become owner of a few more strips of land. . .the dream of most workers is to become bosses. We cannot expect the support of these people unless they know what they are supporting. The process must be slow and gradual and by education and not through violence. All must participate, even the bourgeoisie. Only thus will the people be ready to govern and operate the economy when the inevitable day comes - the many conflicts and contradictions that are built into the very makeup of capitalism will bring about its collapse.

LENIN: You are living in a dream world that is utterly unrelated to life in Russia or anywhere else in this capitalistic world. Education and parliaments are tolerated only so long as they work to perpetuate capitalism and not change it in any way. You are all socialists and most of you are members of well-to-do, even wealthy families, and you are well educated. Now tell me Comrades, where did you become educated in socialism? Was it at school or from books smuggled into prison to you? They will never let the people become educated in socialism. They will pack them off to the Peter and Paul Fortress prison in the middle of the Neva River or to Siberia if they even breathe the word, "socialism." What is implicit in the words "social revolution" is the confiscation of private property. You cannot achieve that without violence because under no circumstances will they relinquish their hold on it. You will never achieve socialism by sitting around in parliaments and talking about and arguing over each step that needs to be taken, the way a bunch of old women do while sewing a bridal gown for a neighborhood daughter. The American Revolution and others succeeded only because capitalism remained sacred. The first thing they will do in an attempt to save capitalism when the inevitable day you speak of arrives, is destroy all parliamentary procedures you have built up and with it all forms of education which helped in the building. What we need to have ready on that inevitable day for taking control, and perhaps giving capitalism a final push over the brink, is not a lot of people sitting around and arguing about what steps to take. . .what we need to have ready is carefully picked and tested, thoroughly dedicated, rigidly-disciplined men and women willing to die for socialism. What we do not need is meddling by the bourgeoisie etc. . .etc. . .

The split dividing the Social Democrats was wider than ever by the time the conferences ended. Both sides continued calling themselves Social Democrats, but the Lenin followers soon became known as Bolshevik! (the plural for bolshevik) from the Russian word, "bolshinstvo" for majority. This was despite the fact that there were far fewer Lenin people at the conference than Martov-Plekhanov followers. The latter became known as Menshiviki from the word "menshinstvo" for minority.

None at the conferences could anticipate that a disastrous war would play a more important part in the collapse of Russian capitalism than its built-in conflicts and contradictions. Neither could Lenin anticipate that a dozen and a half years later he would be talking to a pretty American brunette and saying for publication in American newspapers: "We must admit that we are now a bourgeois state," while explaining why he had been forced to make concessions to Capitalism.

November 7, 1917 (by the new calendar) is when it all happened.

The delegates to the All-Russian Congress of Soviets began trickling into Petrograd slowly on November 2nd, although they were not scheduled to begin the necessary preliminaries until the November 5th sessions. They were to be held in Smolny Institute, before the czar's abdication the country's most exclusive and most luxurious school for the daughters of the wealthiest families. All attempts by the Kerensky people to keep the Congress from meeting failed, despite Kerensky's repeated insistence that only his Provisional Government had the right to call the Soviets into session and that Lenin's call was entirely illegal.

Lenin himself had, by that time, returned from his hiding place in Finland, disguised as an old peasant woman. "What we need, Comrades," he told his fellow-revolutionaries, "is a 'fait accompli.' When the delegates are all in their places we want to be able to say to them: 'Here is the power to rule; what are you going to do with it?'"

He knew that on November 5, the delegates would still be drifting into Petrograd from the far corners of Russia and that there might not be a quorum on hand. On November 6th the delegates would be organizing and wrangling among themselves over the old question of how to bring about socialism in Russia. He therefore decided on November 7th as the crucial day for action. On that day he not only wanted to have the delegates all ready to act, but also wanted to have his Bolsheviki Red Guards in control of the Czar's Winter Palace, the symbol of political power during czarist days and now the place where Kerensky and his Provisional Government were established.

Arrival of the first delegates to the Congress in Petrograd was the signal for the start of street skirmishes. These were between the troops from the Petrograd barracks and the workers' Red Guards on the one hand, and Cossacks loyal to Kerensky's Provisional Government, supported by the Junkers - sons of Russian aristocrats training to be officers. On Kerensky's side also were some two hundred and fifty members of the Women's Death Battalion who, along with the Junkers, were guarding the Winter Palace.

The skirmishes had grown more and more deadly, and by November 5th centered about control of the many bridges over the Neva River, so as to divide the main part of Petrograd from the slums on the industrial side where the workers Red Guards lived. As quickly as the Cossacks and Junkers raised the bridges to keep Red Guards and mobs from crossing, the Red Guards drove them off and lowered them.

Louise and Reed, brandishing their passes from both sides, rushed from one scene of action to another. They buttonholed everyone in sight, demanding: "Chto delayetsah? Chto delayetsah?" (What’s happening? What’s going on here?) They rushed from the Smolny institute to the Tauride Palace where members of the Fourth Duma were still in session. No one seemed able to say anything more than repeat the wildest rumors. Several times they were forced to duck behind smashed and burned trucks to avoid stray sniper bullets.

They returned to the Smolny Institute where there was incredible confusion. To their question, "What's happening?" they received the same reply: "Chort znayet." (The devil knows.) It was late when, completely exhausted, they returned to their hotel room and stumbled into bed.

During the night, while they were asleep, a detachment of soldiers and Red Guards occupied the Telegraph Agency. Half an hour later, the Red Guards took control of the Post Office. At five in the morning, they took over the Telephone Exchange, then the State Bank, and by 10 a.m. on November 6th, the Red Guards and revolutionary soldiers had the winter Palace surrounded.

Louise and Jack awakened late and returned to the Smolny Institute. Then, unaware that Kerensky was by that time on his way to the Front to plead with soldiers to stand by him, they caught a ride on a truck loaded with soldiers on their way to the Winter Palace. Here, the Red Guards, unable to read their passes, refused to let them by. "We saw one group of soldiers who seemed to be confused about what they were supposed to be doing," wrote Louise. "We rushed up to them and Jack waved his passport with its impressive red seals and, shouting in English, 'Official business, official business,' we rushed by them."

Before Kerensky's door they found a young officer pacing restlessly and biting the end of his waxed mustache. He shook his head when Reed said they wanted to see Kerensky. "It is absolutely forbidden," said the officer. And then he added: "In fact, he is not here. He is gone to the Front. And, you know, an odd thing happened. His motorcar ran out of fuel and he had to go through the enemy lines to get some."

They spent three hours in the Palace wandering from one once-magnificent room to another and talking with the Junkers who were most friendly and very unhappy. "Once," wrote Louise, "While we were quietly chatting, a shot rang out, and in a moment there was the wildest confusion; Junkers hurried in every direction. Through the front windows we could see people running and falling flat on their faces. We waited but no troops appeared and there was no more firing, while the Junkers were still standing with their guns in their hands, a solitary figure emerged, a little man dressed in ordinary citizen's clothes, carrying a huge camera. He proceeded across the Square until he reached a point where he would be a good target for both sides and there, with great deliberation, he began to adjust his tripod and take pictures of the women soldiers who were busy turning the winter supply of wood into a flimsy barricade before the main entrance."

Back at the Smolny Institute, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets was now busy. Above the tumult in the huge auditorium the sound of a cannon could be heard, as the revolutionary Cronstadt sailors from the battleship Aurora of the Baltic Fleet, anchored on the Neva River, bombarded the Winter Palace. (The Cronstadt sailors, who played a key role in Lenin’s takeover of Russian power in those historic days, were violently suppressed, and hundreds were killed only two years later when they rebelled against the Lenin people.)

At night, Louise and Jack decided to leave the Smolny Institute to see again what was happening at the Winter Palace. A huge motor truck was just leaving Smolny Institute. “We hailed it," said Louise, "and climbed aboard. We found we had several Cronstadt sailors and soldiers and a man from the Wild Division, wearing his picturesque, long, black cape, as company. They warned us that we would, in all likelihood, be killed, and asked me to remove my yellow hatband as there would be a lot of sniping.

"The mission was to distribute leaflets all over town, especially along the Nevsky Prospekt. The leaflets were piled high on the floor of the truck along with guns and ammunition. As we rattled along the wide, dim-lit streets, we scattered the leaflets to the eager crowds. People scrambled and fought for copies."

The leaflets said:

"Citizens! The Provisional Government has been deposed. State Power has passed into the organ of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies.'"

At a point where the Ekaterina Canal crosses the Nevsky Prospekt they were stopped by soldiers who informed them that they could go no further. They continued afoot to the winter Palace, an occasional sniper's bullet striking the cobblestones in front of them.

They were a short distance from the Palace when they heard a shout: "The Junkers want to surrender." They heard some commands, and silence again. A dark mass began to move forward, the only sounds, the shuffling of feet and clanking of arms. A few bullets whistled by them as they joined the moving mass of Red Guards, but it was not possible to tell from which direction they came. In another few minutes they were out of the shadows and in the light streaming from the windows and open doors of the Palace. "Every window was lit up as if for a fete," said Louise, "and we could see people moving about inside." Then with a great shout, the Red Guards, with Louise and Reed crushed among them, leaped over the firewood barricade and into a great vaulted room, and they were stumbling over the piles of rifles that had been thrown down by the Junkers.

Their closest brush with death came shortly after they had left the main body of Red Guards and began wandering through the many rooms of the Palace. When they reached the room where they had talked with the Junkers they suddenly saw that they were being followed by a group of Red Guards. In another minute or two they were stopped and were surrounded, with the leader, a huge factory worker, demanding to know what they were doing there. They produced their passes. Louise's read:

Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd of Workers and Soldiers Deputies gives Tovarishcha Louise Bryant free passage through the city.

The huge soldier, unable to read, brushed these aside contemptuously and said, "Bah, bumagi (Papers)," and the group began to crowd around them muttering "Provocateurs, looters, Kornilovisti." Then, as the muttering grew more and more ominous and the Red Guards pressed closer, they saw an officer shouldering his way toward them. There followed the longest ten minutes of Louise's life, as the officer, arguing with the Red Guards that he was a commissar of the Military Revolutionary Committee, managed to get them to move off, still muttering ugly threats. When they were gone, the officer, shaky and wiping his sweating face, led them by a side door out of the Palace. "You are foreigners. . .this is very dangerous. . . you nave narrowly escaped being shot."

November 7th. The All-Russian Congress of Soviets was fully organized and waiting for Lenin's appearance and the official opening of the session. It had been scheduled to start at one in the afternoon, but it was almost nine at night when the packed auditorium was shaken by a great roar as the Presidium - the body made up of representatives of all groups taking part in a congress or convention - entered the huge auditorium. With them was Lenin, whom many of the delegates had never seen before in person. "Lenin," wrote Louise, "is not easy to describe. He is sheer intellect - absorbed, cold, unattractive, impatient. In appearance, he is short with a snub nose, little eyes and a wide mouth. He wore pants much too big for him. His power lay in his ability to explain complicated problems in the most simple terms. . ."

Lenin waited patiently until the wild ovation was over and then said in a matter-of-fact voice: "Comrades, let us proceed with the construction of the Socialist Order." Wild with excitement, Louise joined in the great roar that greeted his words.

There was absolute pandemonium. A giant standing beside her, caked mud from the trenches on his tunic, was sobbing, women, with their arms around strangers, were screaming the words of revolutionary songs - the huge hall was a bedlam of noise and motion, while an unsmiling Lenin continued waiting and watching.

Finally it subsided sufficiently for Lenin to say: "The first thing is the adoption of practical measures to realize peace. . .we shall offer peace to the belligerent countries. . .no annexations, no indemnities, and the right of self-determination for all nations."

It lasted for hours; Lenin spoke on and on, referring to notes he had taken from his coat pocket. ". . .all private ownership of land is abolished immediately without compensation. . . until the meeting of the Constituent Assembly, a provisional Workers and Peasants Government is formed, which shall be named the Council of the People's Commissars. . ."

And then the Commissars: President of the Council: Vladimir Ulyanov (Lenin). . . Interior: A. I. Rykov. . . Foreign Affairs: L. D. Bronstein (Trotsky). . . and so on, until, finally: Chairman for Nationalities, Y. J. Djugashvili (Stalin).

(“djugashvili” is the word for steel in the Soviet Republic of Georgia, where Stalin was born. The Russian word for steel is “stal,” with the L pronounced as the two Ls in million. The Russian dictator called himself “the man of steel.”)

Louise described what happened that night as "something tremendous, . . . for some the beginning of chaos and darkness . . . for others the dawn of a new day. . ."

For Russia, it was the beginning of great suffering, starvation and death, which finally compelled Lenin to adopt some capitalistic methods to keep the nation from collapsing. Kerensky's Provisional Government refused to stay overthrown. The rich peasants (kooluks) and estate owners refused to give up their lands and the factory owners wanted no part of workers' committees in running their plants. The generals and admirals and monarchists wanted Russia to be ruled by neither the Germans nor the Bolsheviki, but if they had to make a choice they would rather have the Germans. A surprising number of the Soviets of Workers and the Soviets of Peasants rejected the new order pro-claimed by Lenin, insisting it was premature - too radical.

In Finland, in Siberia, in the Ukraine and in a score of other sections of Russia, White Guards began forming, led by generals with famous names - Kaledin, Kolchuk, Denikin and Kornilov, who had escaped from prison. Thousands of Cossacks and Junkers joined their ranks. . .The troops in many garrisons split three ways - some supporting the Bolsheviki, some insisting on remaining neutral and deserting, the rest, including the officers, joining the White Guards.

Contrary to rumors that Kerensky had been killed, he was very much alive, and before a month had passed, had organized a large army of Cossacks and other loyal to the Provisional Government and was marching toward Petrograd. Bitter battles were fought at Gatchina, a short distance south and west of Petrograd; at Tzarskoe Selo (now Pushkin), and in scores of other places throughout Russia.

Outside of Russia, the November 7 proclamation of Lenin's "Dictatorship of the Proletariat" brought strange developments. Involved in World War One were sixteen nations. Twelve were actively involved on the side of the Allies and four - Germany, Austria-Hungry, Turkey and Bulgaria - made up the Central Powers. The Allies and the Central Powers--waging a war in which millions of people were killed, other millions wounded, and still other millions never accounted for--found something in common - the "Bolsheviki Menace" - which had to be crushed at all costs.

British, French, Japanese and American troops were in Russia by the spring of 1918, the Americans ostensibly to see that the munitions the United States had provided to the czar's armies did not fall into the hands of the Bolsheviki. The Allied nations provided financial help to the counter-revolutionary leaders, while German armies marched deep into Russia to impose a humiliating peace on the Bolsheviki - the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

REPORTER AT LARGE

A Brush with Death: There were few places in the world worse to be in the winter of 1917 than Petrograd. Located at the 60th parallel in a line with the southern tip of Greenland, the mercury frequently dips as far as thirty below zero, and rarely goes beyond fifteen or twenty above. Both food and fuel were hard to find. Exhausted at the end of each day, the bitter cold forced Louise and Jack to sleep either fully or partially clothed. Sex became a rarity, and neither seemed to care much.

"You having fun. Princess?" asked Reed one night.

"Please! No bourgeois titles," warned Louise.

"We're alone; why not?" demanded Reed.

"All right," said Louise. "I don't call what happened today much fun."

It wasn't. In a dispatch to the Philadelphia Public Ledger she described it:

As we turned the corner of Gogol Street and St. Isaac's Square, sniper firing from rooftops started. A man dropped dead in front of the German Embassy building. We ran to the courtyard of the Angleterre Hotel and through the chinks in the fence watched the ridiculously padded-Russian izvoschiki (cabmen) whipping up their horses to get clear of the Square. The dead man's companion was on his knees beside his friend's corpse. He was shaking his fist in the direction from where the sniping came and yelling: "Provocateurs! Hooligans! Kornilovisti!"

As soon as it became clear there would be no more sniper fire, we came out. We could hear gunfire in the distance. It came from where we were going, the telephone exchange building. The Junkers had retaken it from the Red Guards, but now we were across the street, where we were soon joined by a crowd of civilians. Nobody seemed to know what to do next.

Suddenly we saw an armored car in the distance, clattering down the street in our direction. We found ourselves crammed against a huge archway with securely locked iron gates. We hoped the car would go by, but directly in front of the crowd, it stopped with a jerk. Its destination was obviously the telephone building, but we had no way of knowing if they were enemies or friends until it stopped in front of us and its guns began spouting bullets at us. The first to drop was a shabbily dressed worker. He sank silently, a pool of blood quickly spreading all around him. The thing I remember is that no one in the crowd screamed although more than a dozen died.

I remember two little street urchins. One whimpered pitifully when he was shot and then died. The other died instantly, dropping at our feet, an inanimate bundle of rags, his pinched little face covered with his own warm blood. I remember an old peasant woman who kept crossing herself as she whispered prayer after prayer. A man in a shabby fur coat kept saying over and over again: "I am so tired of the revolution."

The hopelessness of our position was just beginning to sink in on me when six giant sailors with the Red Guards, with a great shout, ran right into the fire. They reached the armored car and thrust their bayonets inside again and again. The terrible cries of the victims rose above the shouting and then suddenly everything was sickeningly quiet. They dragged the dead men out of the car and laid them face up on the cobbles. Only the driver of the armored car was still alive. He was begging for mercy and our interpreter screamed: "For the love of God, let him go!" They did.

The Americans: The only place in Petrograd where Louise and Jack were not welcome was the American Embassy. Ambassador David Rowland Francis, former Governor of Missouri, had been provided by the State Department with a record of Reed's radical activities in the United States. Particularly reprehensible to him was Reed's stand on the war and his appearance before a congressional committee to protest President Wilson's demand for conscription. As for Louise, the American Embassy considered her a woman whose urge to be where things were happening made her a Bolsheviki dupe.

Few in the Wilson administration, at home or abroad, shed tears at the abdication of Czar Nicholas. His tyrannical rule, his ineptness, his violent reaction to the most modest demands for reform, his association with the dissolute mystic monk, Rasputin, made him an embarrassment to a nation professedly in a war to save democracy. But Kerensky and most of the groupings of Menshiviki were determined to stay in the war, while Lenin and his Bolsheviki were for ending it no matter what the cost. While it was Ambassador Francis who induced Wilson to recognize the Kerensky government - the first nation in the world to do so - he remained hostile to any form of socialism, including Kerensky's modest plans for bringing it about in Russia. As for Lenin and his Bolsheviki, he was violently hostile to "those anarchists."

Louise described the Ambassador as ". . .without much doubt, one of the crudest and stupidest ambassadors that was ever sent abroad. He never knew anything about Russia, he never tried to find out, and when Jack told him that this was a real revolution, he wouldn't believe it. He kept sending messages to the State Department saying that Lenin was some kind of a socialist or anarchist and of no particular importance. He entertained at the embassy all sorts of Czarist Russians. . .and he sat with his German mistress (Ambassador Francis was 67 years old in 1917) and often drank to the overthrow of the Kerensky regime, the very government he had asked America to recognize."

(Actually, until the United States entered the war, Ambassador Francis represented also, the interests of Germany and Austria with whom Russia was at war, and concentrated on seeing that the soldier prisoners of those two countries were not mistreated. Moreover, despite Louise’s indictment, before he ended his ambassadorship, he pleaded that the United States government adopt a conciliatory course in its relationship with the Bolsheviki, abhorrent though their form of government might be.)

Louise came to know two other important Americans who were officially in Petrograd at the time. Both, representatives of the American National Red Cross, became deeply involved in the struggle between Kerensky's Menshiviki regime and the Bolsheviki for control of Russia. Of the two, Louise became an admirer of Raymond Robbins, one of the few important men in American public life to recognize early that, as between the Bolsheviki and the Menshiviki, it was inevitable that the Russian masses would go with the Bolsheviki.

To William Boyce Thompson, Robbins' associate, however, she developed an antipathy, even though, like Robbins, he was with the Red Cross mission sent to alleviate the wide distress among the victims of war and revolution. A multi-millionaire known as the Montana Copper King, Thompson was convinced that Kerensky was the man best equipped to rule Russia because of his determination to see the world saved from German militarism. He spent a million dollars of his own money to establish newspapers, publish pamphlets, and send speakers to factories and farms to convince the people that their best interests lay in supporting Kerensky.

Leon Trotsky: Louise was with Louis Browne, the correspondent for the Chicago Daily News and New York Globe, when they interviewed Trotsky.

"He seemed far less relaxed than when I first saw him in New York," she reported. "The revolution, at the time he lived in New York, was still a dream and he did not have on his shoulders the tremendous responsibilities he now had as Commissar of Foreign Affairs - the Number Two man in the government. He and his wife live in the attic of the Smolny Institute, a one-room apartment with two cots, a cheap dresser and three wooden chairs."

He was slight of build, wore thick glasses, had a high forehead, a thick black mustache and a tiny goat-like beard. He impressed her tremendously.

Trotsky, said Louise, was an internationalist. He did not make nationality or economic or social status a condition for salvation. Along with Lenin, he insisted that Marxism was the way to salvation for the property less and exploited, whether they lived in New York, London, Brazil, Bucharest or on the wrong side of the Neva River in Petrograd. To him, that is what the Marx-Engels cry, "Workers of the world, unite," meant.

He believed with equal fervor that a socialist nation could not exist as an island surrounded by capitalist countries, because capitalism, by its very nature, must keep expanding in order to survive. This was in sharp conflict with Stalin's view of "one state socialism."

It was a vision, however, that began to fade as the workers of Europe, in one country after another, rejected the Lenin-Trotsky appeal for the overthrow of capitalism.

Kerensky: She talked with him only three days before he fled from the Czar's Winter Palace where he had been living. She was with Jack Reed and an Associated Press man and wrote two versions of the interview, one published in American newspapers, and the other - a most unorthodox version - for what was to have been the story of her life with John Reed.

In the newspaper-published version, Louise wrote:

"He was a sick man and in great pain. He had to take morphine and brandy constantly to stay alive. We entered the beautiful little library of Nicholas II. Kerensky lay on a couch with his face buried in his arms, as if he had suddenly been taken ill and was completely exhausted. I had time to note some of the Czar's favorite books. . .various classics and a whole set of Jack London in English."

"I had a tremendous respect for Kerensky," she said. "He tried so passionately to hold Russia together, and what man could have accomplished that - at that hour?. . .He attempted to carry the whole weight of the nation on his frail shoulders, keep up a front against the Germans, keep down the warring factions at home. Faster and faster grew the whirlwind. Kerensky lost his balance and fell headlong. . ."

It was perhaps Kerensky’s key role, in the great Russian drama which she was attempting to portray for the readers of her articles in American papers, that kept her from reporting lighter aspects of the interview. In any event, in the unpublished version she reported that when they introduced themselves to

Kerensky he apologized for not getting up from the couch, saying that he was in great pain because of a kidney infection. Jack Reed was sympathetic, informing Kerensky of his own kidney problem. "There they were," wrote Louise in her notes, "talking about their aches and pains their kidneys created for them, like a couple of old women, while outside events were developing that would change the world."

"The women Maria Spiridonova looks as though she came from New England. Her puritanical plain black clothes with a chaste little white collar, and a certain air of refinement and severity, seem to belong to New England rather than to mad, turbulent Russia, But she is a true daughter of Russia and of the revolution."

Thus Louise described one of the great women martyrs of the Russian revolution. There were others, and talking with them of their achievements, bolstered her determination to fight harder than ever for women's political rights in her own country.

"Her early history as a revolutionist," said Louise, "is exceptional even to the Russians who have grown used to great martyrs. She was nineteen when she killed Lupjenovsky, the governor of Tambov. He had a dark record. He went from village to village, taking an insane delight in torturing people. When peasants were unable to pay their taxes, he made them stand in line for hours in the cold and then ordered them publicly flogged. He ordered his Cossacks to commit the worst outrages against the peasants, especially the women."

"Marie Spiridonova decided to kill him. One afternoon she saw him in the railway station. The first shot she fired over his head to clear the crowd, the next she aimed straight at his heart. Lupjenovsky dropped dead."

"First the Cossacks beat her; then threw her naked into a cold cell. They came back and demanded names of her comrades. She refused to speak, so bunches of her long, beautiful hair were pulled out, and then she was burned with cigarettes. For two nights she was passed around among the Cossacks like a bottle of vodka. They sentenced her to death and then changed the sentence to life imprisonment. She was sent to Siberia. When the revolution broke out eleven years later, she was freed."

"I asked her how she managed to keep from losing her mind during the eleven years in Siberia. She smiled: 'I learned languages. You see, it is a purely mechanical business and therefore a wonderful soother of nerves. It is like a game in which one gets deeply interested. I learned to speak English and French.'"

"I wanted to know why more women did not hold public office since Russia is now the only place in the world where there is absolute sex equality. Spiridonova said: 'You know, before the revolution, as many women as men went to

Siberia; some years there were even more women than men. . . but going to Siberia is a different matter from holding public office. It needs temperament and not training to be a martyr. But in politics, men accept positions because they are elected and not necessarily because they are fitted for them. I think women are more conscientious. Men are used to over-looking their consciences - women are not.'"

Alexandra Kollontay: "Before she was appointed the first Minister of Welfare by the Bolshevik regime, she had written a dozen books on sociology, with special emphasis on mothers and children. (She also became the world’s first woman ambassador in 1927 when she was named the Soviet Union’s ambassador to Mexico.) I saw her often, first as a correspondent, and then as a friend. One day she confided to me that there were many things Lenin did with which she disagreed - some even distressed her. But in the struggle for freedom against the reactionaries she would never desert the proletariat and its champions, even if they made every mistake on the calendar."

"One day when I came to see her, a long line of old people were outside her door waiting to see her. They had come as a delegation from an old people's home to thank her for having removed those who had been supervising them so that they could now make their own decisions. 'They now elect their own officers and have their own political fights. . .they even decide what should be on the menus,'" said Alexandra Kollontay proudly. I said, but what can the menus consist of in these days when so little is available? She laughed: 'Surely, you must understand that there is a great deal of satisfaction in deciding for yourself whether you want thick cabbage soup or thin cabbage soup.'"

Tamara Karsavina: (She was the brilliant Russian dancer, successor to Anna Pavlova as premiere danseuse at the Imperial Opera House in 1910.) "She was the most beautiful dancer in the world. I saw her dance in those meager days for an amazing audience - an audience in rags, an audience that had gone with- out food to buy the cheap little tickets."

"When she came on, it was as hushed as death. And how she danced! And how they followed her! Russians know dancing as the. Italians know their opera. 'Bravo! Bravo!' came from several hundred throats. And when she finished, they would not let her go - again and again and again she had to come back until she was wilted like a tired butterfly. Twenty, thirty times she returned, bowing, smiling, pirouetting, until we lost count. . .when it was over at last, the people filed out into the damp winter night, pulling their thin overcoats about them."

SOMERSET MAUGHAM

Among her weirdest experiences, certainly among her most unusual in those strange and unusual days in Russia, was her meeting with Somerset Maugham, the British author and playwright whose sensational book, "Of Human Bondage" had come out only two years earlier. When Maugham turned up in Petrograd a month or so after the Lenin takeover, he made it a point to look up John Reed, whose articles about Pancho Villa and his bandit-rebels had interested him. He invited John and Louise to have lunch with him.He seemed particularly interested in Reed's background, his parents and grandparents, and his conversion to radicalism, and asked if it was true that

Reed was not only collecting material for a book about the revolution, but that he had also become active in the Bolsheviki propaganda division. Reed said he was, that he planned to write not only an account of the revolution itself, but a series of books about it.

"An odd thing about Mr. Maugham," wrote Louise in her notes about the meeting, "was that he was fond of playing pranks and said the most preposterous things. Every now and them, through-out lunch, he would turn to me, glance about mysteriously and in a low voice say: 'You won't of course, reveal that you had lunch with a British Secret Agent, will you?' I laughed. Of course not, I said. It was so ridiculous. It couldn't have been funnier if he'd said he was an ambassador of the Pope and was in Petrograd to convince Lenin that religion was not the opium of the masses. Or again: 'You will forgive me if I make an occasional note on this leaflet in secret code?' Jack was enjoying Mr. Maugham's attempt to pretend he was a secret agent as much as I was."